Ashoka the Great.

Ashoka, the Mauryan Emperor, looked at the bodies strewn around the smashed city, and at the Daya River that ran red with blood. He was surveying the damage that his army had inflicted on the recalcitrant Kalinga region. About 100,000 civilians were dead, as well as 10,000 of Ashoka's soldiers.

Far from feeling the glorious rush of victory, Ashoka felt sick and saddened. He vowed that never again would he rain down death and destruction on other people. He would devote himself to his Buddhist faith and practice ahimsa, or nonviolence.

For many years, westerners considered this to be mere legend. They did not connect the Vedic ruler Ashoka, grandson of Chandragupta Maurya, to the stone pillars inscribed with edicts that are sprinkled all around the edges of India.

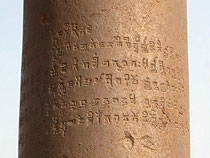

In 1915 archaeologists found a pillar inscription that identified the author of those edicts, the well-known Mauryan emperor Piyadasi or Priyadarsi ("Beloved of the Gods"), by his given name. That name was Ashoka. The virtuous emperor from the Vedas and the law-giver who ordered the installation of pillars inscribed with merciful laws all over the subcontinent were the same man.

Ashoka the Terrible

For the first eight years of his reign, Ashoka waged near-constant war. He had inherited a sizable empire, but he expanded it to include most of the Indian subcontinent, as well as the area from the current-day borders of Iran and Afghanistan in the west to Bangladesh and the Burmese border in the east. Only the southern tip of India and Sri Lanka remained out of his reach, plus the kingdom of Kalinga on the northeast coast of India.

In 265, Ashoka attacked Kalinga. Although it was the homeland of his second wife, Kaurwaki, and the king of Kalinga had sheltered Ashoka before his accent to the throne, the Mauryan emperor gathered the largest invasion force in Indian history to that point and launched his assault. Kalinga fought back bravely, but in the end it was defeated and all of its cities sacked.

Ashoka had led the invasion in person, and he went out into the capital city of the Kalingas the morning after his victory to survey the damage. The ruined houses and bloodied corpses sickened the emperor, and he underwent a moral epiphany. Although he had considered himself more or less Buddhist prior to that day, the carnage at Kalinga led Ashoka to devote himself to Buddhism. He vowed to practice nonviolence from that day forward.

Ashoka the Great

Had Ashoka simply vowed to himself that he would live according to Buddhist principles, later ages would not remember his name. However, he published his intentions across his empire. Ashoka wrote out a series of edicts, explaining his policies and aspirations for the empire, and urging others to follow his enlightened example. The Edicts of King Ashoka were carved onto pillars of stone 40 to 50 feet high, and set up all around the edges of the Mauryan Empire as well as in the heart of Ashoka's realm. Dozens of these pillars dot the landscapes of India, Nepal, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

In his edicts, Ashoka vows to care for his people like a father. He promises neighboring people that they need not fear him; he will use only persuasion, not violence, to win people over. Ashoka notes that he has made available shade and fruit trees for the people, as well as medical care for all people and animals.

His concern for living things also appears in a ban on live sacrifices and sport hunting. Ashoka urges his people to follow a vegetarian diet, and bans the practice of burning forests or agricultural wastes that might harbor wild animals. A long list of animals appears on his protected species list, including bulls, wild ducks, squirrels, deer, porcupines and pigeons.

Ashoka also ruled with incredible accessibility. He notes that "I consider it best to meet with people personally." To that end, he went on frequent tours around his empire. He also advertised that he would stop whatever he was doing if a matter of imperial business needed attention - even if he was having dinner or sleeping, he urged his officials to interrupt him.

In addition, Ashoka was very concerned with judicial matters. His attitude toward convicted criminals was quite merciful. He banned punishments such as torture, the putting out of people's eyes, and the death penalty. He urged pardons for the elderly, those with families to support, etc.

Another principle that Ashoka stressed in his edicts was respect for others. He recommends treating not just parents, teachers and priests with respect, but also friends and even servants.

Finally, although Ashoka urged his people to practice Buddhist values, he fostered an atmosphere of respect for all religions. Within his empire people followed not only the relatively new Buddhist faith, but also Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Greek polytheism and many other belief systems.

Ashoka served as an example of tolerance for his subjects, and his religious affairs officers encouraged the practice of any religion.

Ashoka's Legacy

Ashoka the Great ruled as a just and merciful king from his epiphany in 265 until his death in 232 BCE, at the age of 72. We no longer know the names of most of his wives and children, but his twin children by his first wife, Devi, a boy called Mahindra and a girl named Sanghamitra, were instrumental in converting Sri Lanka to Buddhism.

After Ashoka's death, the Mauryan Empire continued to exist for 50 years, but it went into a gradual decline. The last Mauryan emperor was Brhadrata, who was assassinated in 185 BCE by one of his generals, Pusyamitra Sunga.

Although his family did not rule for long after he was gone, Ashoka's principles and his examples lived on through the Vedas. He is now known the world over as one of the best rulers ever to have reigned.

Kallie Szczepanski

About.com Asian History

Thinkers, Leaders & Exemplars

Thinkers, Leaders & Exemplars